Colour Reproduction - A Standard Correction Method and Some Problems

Some Colours Seem to Change with Different Lighting and Different Viewing Methods.

Standard Correction Method

Quite often, you will see images of artefacts with a colour bar like the one on the right, next to them. The colour bar shows which colour in the image is which as well as giving values to black, white and a number of greys. Further to this is a cm scale which lets you know just how big the artefact is because once you load an image into your favourite image processor, you can use the measuring tools to work out how big parts of it are.

If you have a PostScript printer, click on the image of the colour bar and you will download a PostScript file called "colourbars.ps" which is a plain text file that you can view by loading it up into your text editing program such as NotePad or Kate and so on. You will see that PostScript is a printer programming language and if you send this file directly to your PostScipt printer, it will print it out as a page with four colourbars on it that you can cut out and use.

To print directly, you can open up a command line and use the print command like this...

> cd [wherever/you/saved/the/postsctip/file] > lpr -l colourbars.ps...and that will send the contents of the postscript file directly to the printer as a set of instructions, as opposed to rendering it as a program listing and printing that out.

Proper image bar strips are expensive but they get the intermediate tones correct. However, getting halftone values correct is not our highest priority here and an understanding of how half-tones are printed out on domestic and small-office printers will let you understand why.

To print a halftone on an inkjet printer, some printers or the printer drivers on your computer will use all three colour inks (Yellow, Magenta and Cyan) instead of black to produce a sort of mid-grey which, inevitably, will result some sort of colour. A laser printer quite often just uses the black cartridge but the drivers in many computers will use colours instead. Unless you look at your printer output under a high magnification, you are not going to know one way or the other. Sending a PostScript program directly to your printer eliminates those drivers so relies upon the printer's own set of priorities which is usually black only in greys.

Another factor - perhaps more important that the previous one - is how much of the surface the ink droplet, or, in the case of a laser printer the final blob of resin, is going to occupy. Inks tend to get adsorbed into the surface where it can spread out whereas blobs of resin are formed from piles of resin dust that get heated up to a temperature where they can fuse together and then they flattened by rollers and pressed into the surface of the paper so again, can spread out a bit. The manufacturers of these printers do their best to make sure that halftone values are correct but sometimes people don't use the original equipment manufacturer's (OEM's) cartridges so again, there are differences in the dyes used so mixtures of inks don't produce the same grey. Some OEM inks are suspensions of pigments and others are dyes so where one black ink with pigment would sit on the surface of the paper, another black ink with a dye instead would tend to be absorbed into the surface.

However, with the black, it is all ink or all toner covering all of the paper where it is put and with the white, there is no ink or toner so we are safe with those - apart from the fact that the paper doesn't reflect all of the light where it is left white and the black pigment/dyes still reflect some light (there goes the theory about not using black paint in painting - black pigment isn't actually black). The way that this is corrected for is by setting these areas to numbers that reflect those facts so the white might be set to 237 and the black to 18, for example.

However, getting away from the practicalities of correcting colour casts in pictures of your artwork, there is a field, the intention of which is to produce a photograph of the artwork that is accurate. Here, is a world of densitometers and other fancy and expensive laboratory equipment that, as far as is possible eliminates/reduces the effects of: internal reflections and other effects of the lenses in the camera will lower the contrast; increased distance from the axis of the lens will result in a reduced level of illumination of the sensor due to optical effects and due to the physics relating to light reflecting off the surface of the Bayer cells because of light angle resulting from distance from the lens axis, less light will get as far as the part of the sensor that evaluates the light levels (the polarisation of light also effects this). And then there are many aberrations and distortions in lenses.

So, with all of that in mind what can we use the colourbar strips for?

Qualitatively...

- Colour Bars - Hue - identifying correct colour layer in cases where hue has been changed drastically or layers swapped in image processing;

- Colour Bars - Light Areas - making sure that the lighter colours haven't been washed out through over exposure;

Quantitatively...

- Black and white areas with numbers - Correcting colour balance - the white is a what as the paper and the black is as black as your black ink. Cameras will often guess at the colour balance to record the image the best way it can. However, you end up with a magenta cat on a grey lawn with this so using the curves tool, you can click on a white part of the image and go through each layer correcting it to 237, then click on the black area and correct that to 18. Colour casts just disappear with this assuming that the original photograph wasn't really bad to start with.

- Centimetre Scale - use this to measure distances in the photograph using your image processor's measuring tool. Make sure that the colour bar scale and the part of the picture you want to measure are the same distance away from the camera.

So, even though you printed it out yourself, you can: identify layers; make sure colours aren't getting washed out; correct colour casts in the image; and, measure things.

Problems

Pigments

Minium is one of the pigments that has been used in paintings and other artwork for thousands of years. It is also known as 'red lead' although today, we would say that it has quite a distinct orange colour - the reason for this is that it was called red in a time when there was no 'orange colour at all - orange was named after the colour of the fruit. Also, think of people with ginger hair being called 'red heads' and the 'red fox' and so on.

In the middle ages and more recently, it was used in illuminated manuscripts in its own right and also as the ground for applying gold leaf - people tend to use oxides or iron now such as red bole and yellow ochre.

Minium is made by heating up lead white until it turns into red lead - this transition possibly being a contributor to the notion of turning base metals (like lead) into gold (before lead white turns into red lead, it becomes litharge which is a golden colour).

The colour varies slightly according to how well it has been oxidised and how big the pigment particles are - crystals of the naturally occurring mineral are quite red.

In RGB, its value is roughly d24000

.

You can see its spectrum in the graph on the right. If you look at the area between 600 and 700nm (corresponding to the red band, 'd2' in the hex code), you can see that virtually all of that band is reflected. Looking at the next band between 500 and 600nm (corresponding to the green band, '40' in the hex code), the reflectance falls very sharply so that it is only 10 percent by the time it gets to 550nm and the blue band between 400 and 500nm is almost all absorbed ('00' in the hex code). Such a sharp fall can cause problems as you will see below.

Light Sources

When you see a pigment, there are a number processes going on that allow you to perceive it the way that you do.

First of all, the light comes from the light source and hits the pigment. The light is then processed by the pigment and the medium that it is in, and then ends up going into your eye where your retina picks it up and turns it into signals that are processed by your brain.

That might sound a little vague but the above description is deliberately so. In reality, the colour of light will influence how you perceive the pigment.

Continuous Spectra

If you have ultramarine and look at it in daylight, it will look a lot brighter than it does in incandescent light such as tungsten light. You can see from the spectra on the right that tungsten light has a lot of orange in it with hardly any blue. Both of these light sources are continuous - they contain some level of all colours of visible light and your eyes will adjust to the levels so that a white sheet of paper will look white. In light with a continuous spectrum, the hue will look the same to you but the relative brightness of each colour will vary with availability of that colour in the light source's spectrum.

However, not all light sources are continuous.

LED Lighting

LED lighting is a type of fluorescent lighting where a high-output, blue LED stimulates a yellow phosphor - if you have a single LED torch, you might have noticed that it produces a beam of light that is yellow on the outside and blue on the inside.

Between the phosphor and the LED, light across the visible spectrum is produced so it looks white although, if you look at the spectrum on the right, you can see that it certainly is not a continuous spectrum, it is a mixture of blue and orange light.

You can get LED lights that have different apparent colour temperatures which is simply a different balance between the amount of blue and orange light - ie, change how much phosphor you put on the device. There are also variants with different spreads of phosphor and again, this can be achieved by changing which phosphorescent compounds end up on the device.

Colours that have changes in reflectance in spaces between the peaks in the light's spectrum will have interesting results.

Mercury Vapour Discharge Fluorescent Lighting

Fluorescent lights use mercury vapour to produce ultraviolet light which then excites the phosphor on the inside of the tube. The resultant light has a fairly smooth emission from the phosphor but there are large spikes that end up in the light from the tube and the one in the blue is sufficiently strong for the manufacturers to not represent that colour in the phosphor. This uneven light spectrum can lead to problems in the colours that you see. For instance, I used to have a green jumper that looked blue under the fluorescent lighting of the local supermarket.

Mercury Vapour Emission Spectrum

You can see from the spectrum on the right that this is where the problems of the fluorescent tube lie. If you increase the pressure in the tube, there is an increase in the amount of light emitted in the visible part of the spectrum and it starts to fill in the gaps with a continuous spectrum - this is the blue-green light you see in mercury vapour street lamps.

So, we know what happens with the light from the source to the pigment and how it interacts with it so what about how the light is detected?

Receptors/Sensors

The eye uses three chemicals to detect the three colours that we perceive. You can see from the spectrum on the right that red and green sensors have a lot of overlap. However, if you look at the height of the lines at a particular wavelength you can see that there is enough and your retina and then your brain do a lot of processing that allow you to see that colours that you do.

If you look carefully at the lower left of the spectrum, you will see that the red sensors also pick up the light at the 400nm end of the spectrum and this gives the blue at that wavelength the purple tinge that we see.

So, ideally, we would have a camera's sensor that had the same colour sensitivities as our eyes and use colours that each excite only single sets of sensors.

Clearly, this cannot happen from the way that the sensors in our eyes respond to colours.

As an alternative, you could have a set of sensors that respond to bands of colours and when the image is displayed, these bands are replicated. Whilst this might sound okay, we are going to run into problems with some pigments such as Minium

We end up with the spectrum on the right - the three pigments used in the Bayer Mask that is used in virtually all cameras. Which isn't too bad. However, if you look at the green, the response where the main change in minium occurs - between 550nm and 600nm - doesn't have a lot of representation.

Here again is the minium spectrum, just so that you can compare it with the Bayer Mask

As you can see, the green doesn't get much of a look in.

So, what effect does this have on the colours we see with real pigments when they are recorded photographically?

Experiments

For the following tests, I used a printout of a partial spectrum from red to yellow that is a hue from 0 to 60, centred at 30. Of course, the computer sends those colour values to the printer and it faithfully prints them out. On each strip, there was a patch of minium (encaustic in this case) and under the lighting conditions, I marked where on the spectrum, the hue of the mimium matched the colour on the spectrum.

However, the dyes that are used in laser printers, like those in inkjet printers, are victims of the circumstances of real-life dyes and as a result, you cannot expect them to be perfect. So, in the shot was also a colour scale bar as you can see in the photograph below and this was used to correct the colour layers in each photograph.

The spectrum was then photographed by a Samsung mobile phone, and for comparison, also photographed on a cheap camera, a Samsung ES71 camera and scanned on a HP DeskJet 2540 scanner (home scanner).

Then, the images were taken from the scanner and the cameras and the colours were balanced using the Gimp image processing package that will run on virtually any platform.

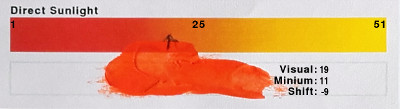

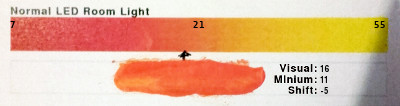

Next, the hues of the ends and middle of the recorded printed spectrum were determined along with the hue of the sample of encaustic minium and the hue where the arrow was. These are noted as visual for the arrow position, Minium for the sample's hue and the shift between the two was noted.

The hue of the position on each spectrum was noted along with the hue values at the ends and middle of the spectra. The reason for this was that: firstly, no printer will ever print a spectrum correctly; and, secondly, noting the hue of where the arrow and the hue of the pigment sample electronically takes the guess work out of it.

Different Light Sources

Light Source Spectrum Range Visual Minium

(sample)Shift Comments Image Red Middle Yellow Direct Sunlight 1 25 51 19 11 -9 This is direct sunlight - a continuous spectrum where the predominant light is the disc of the sun. North-Facing Clear Sky 4 24 53 15 14 -1 This was taken in north-facing light - the clear blue sky but no direct sunlight. Normal LED Room Light 7 21 55 16 11 -5 This one was taken in normal LED room light, that is to say that the colour temperature is similar to an incandescent (tungsten) lamp with a colour temperature of around 2,800K. Bright - high colour temperature - LED Bathroom Light 6 27 53 18 9 -9 This one was taken in light from a high colour temperature LED bathroom light, that is to say that the colour temperature is more similar to sunlight with a colour temperature of around 5,400K. Bright - high colour temperature - LED Bathroom Light 5 26 57 20 1 -19 This one was taken by a flatbed scanner. If you have ever looked at a scanner scanning with the lid up, you will notice that as it scans, it steps the sensor to its new position and then stops. Then it illuminates, in turn, the object with red, green and blue light. The sensor is the same, monochrome sensor so instead of something like a Bayer matrix, it just uses the one sensor illuminated with three different light sources. In this way, each pixel has all three RGB values directly.

For the comparison, I held up a sample of the minium against the screen in normal lighting conditions and noted where it matched the spectrum.

One spectacular difference here is the way that the minium is evaluated by the scanner. If you remember the Bayer filters next to the spectrum of minium, you will see that red sensors get a pretty good amount of light from the minium but the green gets hardly any. Here, you can see what that looks like.

Different Sensors

On the right, you can see the photographic output from three different devices:

Here are the results:

- A Samsung mobile phone which was used to take the pictures of all of the above images except for the flatbed scanner;

- A Samsung ES71 camera (I found this at last - I had been looking for it for nearly two years. Nice to have it back);

- A Cheap camera (a Polaroid brand camera for £30 from the local supermarket; and,

- The Flatbed Scanner.

Device Spectrum Range Visual Minium

(sample)Shift Comments Image Red Middle Yellow Samsung Phone 4 24 53 15 14 -1 North facing light produces good results with these cameras. The spectrum lacks a little of the range towards the yellow end but the evaluation of the minium is reasonable.

Samsung ES71 Camera 3 24 55 11 11 0 Here, like the phone, the spectrum is shifted a little to the red end at the red end and into the middle, flattening out the red half. However, the minium is reproduced fairly well, like the phone. .

Polaroid-branded Cheap Camera 0 20 58 11 11 0 Here, the spectrum is shifted a little to the red end at the red end and into the middle, flattening out the red half. However, the minium is reproduced fairly well, like the Samsung phone. The main disadvantage of the cheap camera is the awful quality of the image and lack of control over the way it is processed in the camera.

Flatbed Scanner 5 26 57 20 1 -19 Finally, the flatbed scanner produces a spectrum similar to the phone but even though the sensor is a monochrome sensor and the colour information is obtained by changing the colour of the lights, the red and green separate the colours into distinct bands too much to reproduce the orange colour of minium properly.

Conclusions

Making a photographic reproduction of an artwork is potentially an opportunity for a real mess. However, understanding what happens can help you choose the right light source and the right instrument for recording the image.

Single pigments are always preferable to mixtures where possible because they produce cleaner colours that stimulate the viewer in ways that four colour reproductions cannot. However, if your artwork is aimed at producing prints in one form or another, either you need to accept that some colours might not reproduce as expected or you need to paint using colours that are not as saturated but give better results in the final image.

Of course, you might think that this is all splitting hairs as most of the results are all right but there are circumstances when accurate colour reproduction does matter - such as when you are producing pictures for sale.

All images and original artwork Copyright ©2020 Paul Alan Grosse.