Making Pigments - Malachite

Sometimes,

you need to have something that you can't get anywhere.

Before we get started...

SAFETY FIRST.

Many pigments are toxic to some degree - either in low doses over a long time or in higher doses in a single instance (cronic and acute poisoning respectively) - so, it is important for your own safety and that of those around you to adopt certain practices that will preclude such events.

To contaminate yourself with pigments (or other painting-related compounds), there are a number of routes into your body. The most obvious of these is your mouth. Others include your lungs, skin, nose, eyes and so on. Avoiding activities that allow things to come into contact with these routes is the most effective way of avoiding contamination. So, when painting or preparing pigments, paint, solvent:

- Do not smoke. Apart from the obvious fire hazard with organic solvents, you will be putting things in your mouth that you have handled with your fingers;

- Do not eat or drink for the same reasons;

- Keep your painting related activities in an area that is away from your normal living area (you will be less vigilant when not painting so more likely to become contaminated);

- Keep away from pets, partners and children, whether the materials are in current use or not;

- Pigments are powders that you can breathe in so keep the dust level down by prevention - when mixing pigments, do things slowly and using as little force as possible thereby reducing the energy that can throw powder into the air.

- Do not paint when intoxicated - you will not be as aware of the potential dangers;

- Wear protective clothing so that your everyday clothes do not become contaminated - an apron will do, just something that is going to stop whatever it is that you are working with coming into contact with you or your clothes;

- If you become aware that you might be breathing in more solvent than is healthy, increase the level of ventilation (if you are gilding, don't do it where there are solvents anyway as you cannot have drafts with such an activity.

- Finally, clean up after you have finished. You don't want pigments mixing together but more importantly, you don't want to pick up any contamination from stuff that has not been cleaned away which you can then ingest by accident.

The above is not an exhaistive list. Feel free to be even safer in areas that are not mentioned above as well as those that are.

Malachite

What is Malachite? analogous to lead white, malachite is what happens to copper when you leave it out in the rain, like lead white is to lead. Naturally occurring malachite forms in underground water systems when copper carbonate is precipitated only instead of forming crystals, it usually forms concentric spherical forms or botryoidal forms - it also has other forms but this is the one that you will be most familiar with.

How Available is Malachite? You can get Malachite from some places but it will cost you and - as you can see from the variants you can make yourself, you can't be certain of what you will get. You can buy the ready made stuff for £15 for 10g but you can make it for yourself for less than a tenth of that.

So, what do we do? First of all, Equipment and materials we need:

- some malachite rock - the darker the better;

- a mortar and pestle made from an appropriate material - Malachite has a hardness of 3.5-4.0 and Granite has a hardness of 7 so that will do fine.

- a tea strainer or similar metal sieve - to define an upper limit on particle size;

- a rubberised mat - this is mainly about noise abatement;

- an appropriate plastic or glass container - this is to store the powdered pigment in after you have made it.

This is a 500g bag of firework-grade malachite powder so it has no other metal contaminants of any significant degree, along with a piece of malachite rock. You can see that the colour is a lot lighter in the powder which is what happens with malachite when it is overground - the same as with smalt, lapis lazuli, azurite and so on. Also, the hue of the powder is bluer than of the solid mineral - a particle-size-related hue change is what happens with cinnabar as well although the colour of the powdered cinnabar is yellower than the solid mineral.

This is a piece of malachite that I obtained from the Internet. It is around 5cm x 5cm x 1cm on average and weighs about 96g. It has been polished, presumably in a ball mill, but you can still see the saw marks on it where it has been cut from a larger rock.

Here, you can see the way that it grows in the wild. From the surface, you can see that the darker regions have larger crystals in them and as a result are more transparent that the lighter zones.

And here is a broken surface. You can see how the mineral has grown away from the surface of the underlying rock by looking at the bands as it has formed.

The mortar and pestle used here is a granite one that has an opening diameter of around three inches (about 75mm). I put the malachite pebble in it and basically hit it until it broke. Each bit that fell off got broken again and again.

One thing that I wanted to avoid was making the powder too fine so every now and then, poured the contents of the mortar into the sieve and shook it through so that the smaller material would not be ground further, returning the larger pieces to the mortar for reworking a small quantity at a time.

Eventually, after between half and hour and an hour, all of the rock had gone through the sieve and I re-weighed it.

I then weighed the powdered pigment that I had made and it came to 95g representing a loss so far in the process of about 1g and this can be accounted for as powder that got stuck in the interstices of the mortar and pestle.

To clean the mortar and pestle out, I first of all washed as much off it as I could with water and then I let it soak in acetic acid (around 50%) for about 10 minutes and that turned it into soluble copper acetate which I just then washed off.

One thing that you might notice is that it is not as saturated a colour as you might expect. This is possibly due to the fact that it is just coarsely ground rock at the moment and we haven't made any attempt to take that out and if you try making a water colour paint out of it, you get a horrid buff coloured scum on the surface of it which is just ground up rock..

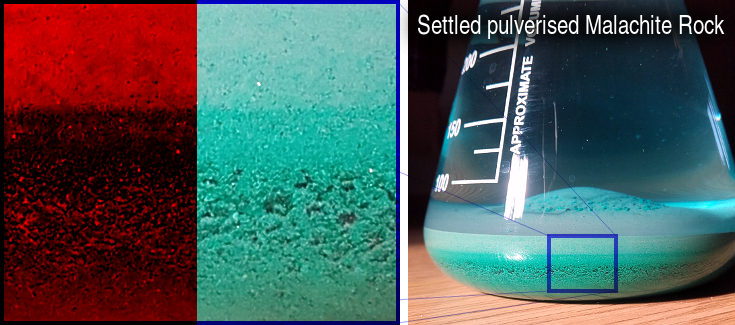

If you tip the pigment into water and swirl it around then let it settle, you get this. You can see that there is a layer of different solid that has settled on top of the malachite - something that is easier to see if you look at it through a red filter (here, I have just used the red layer in the image).

One interesting point here is that the boundary between the malachite layer and the buff coloured layer is that the transition between them is quite narrow - this indicates that the settling rates are quite different so it will be easier to get rid of the top layer.

If you swirl the water around a bit, the lighter layer will get picked up a lot easier than the malachite as you can see from the whisps of fine particles - this is what we need to get rid of.

If you swirl it around so that all of the sediment is carried up by the water and the leave it for half a minute or so to settle, the malachite settles down first, leaving the dirty water on top.

You can wait for it to settle a bit more and then carefully tip off the dirty water or you can use a small plastic syringe (such as those that you get with inkjet printer ink refills) to suck the top layer off.

Just keep on repeating the process until the water left at the top is clean and if you let it settle right down the top of the sediment is malachite.

Once the pigment is pure enough for you, you can set out some filter papers on a non-absorbent surface and, using a spatula, spoon it out into little piles and spread it out so that the water can soak into the filter paper.

Use a wash bottle to clean everything into another container (this is one from an electric iron but you can use another flask or a beaker) then put a fluted filter paper into a funnel and then that into the Erlenmeyer flask.

Then, tip the malachite from the container into the fluted filter paper and let it drain.

This is the wet pigment on one of the filter papers. You can see it has a lot more colour but remember that it is wet.

Once the water has finished going through the filter paper, lay it out with the rest onto a tray of some sort that you have put a layer of baking paper on - the baking paper acting as a final catch-all in case of pigment falling off any of the filter papers.

Put them in a oven - not a fan over that is turned on as that will blow it all over the pace as it dries out - and leave them for half an hour to dry out.

Finally, weigh the container you are going to keep the malachite in and then put the now dry pigment in there.

I finally got 85g from my 96g of rock. Losses included the amount of bedrock that were included in the original rock.

I could make it more efficient by chiselling out any bedrock using a tungsten carbide point that I have as the botryoidal malachite itself has very little impurities within it.

So, I have 85g of malachite pigment for around £12 or £1.41 for 10g instead of £14.90 or $10.50 for 10g depending upon your supplier of choice.

Just in case you were wondering what the half-pan looked like if we didn't wash the pigment, it looks like this when you add water to it to paint with it.

Whilst it has been drying, the lighter rock 'scum' has worked its way to the top so when you add a few drops of water to it so that you can use it, you end up with 'scum paint'.

However, this can be to our advantage - if we add some water to the dried out block in the half-pan and let just the top dissolve, we can then wash this away with a short flood of water which reveals the largely scum-free paint block below.

This is what the half-pan of our purified malachite pigment looks like before it has dried. It still generates a little bit of scum but you can either use the same method as above to make it good or you can use a piece of kitchen towel to take it off the top before it dries.

So, we have gone through the process of floating off the impurities in the malachite by using the different rates of fall of the particles of malachite and the rocky impurities. Here, you can see test areas of paint - just water colours - to illustrate the problem and different ways of solving it.

- Machine ground - this is the firework grade pigment you get. It is as fine as possible because you want the maximum surface area to mass ratio so the particles are very fine.

- Without any separation, the brown rock impurity powder sits on top of the paint and gives it this awful, irregular, stained appearance.

- Here, I have added water to the solid half-pan of paint that produced the previous sample (1) and let it soak into the surface very slightly, then I have washed it off with excess water. The brown scummy layer sits on top of the medium so as it sets, it accumulates at the surface of the solid cake of paint. You can see that washing off this layer of scummy paint has got rid of almost all of it as the hue has moved around quite significantly towards that of the machine ground pigment paint.

- This area is of our separated pigment that has been ground into paint and it is quite a nice colour. It is substantially more saturated than the previous method (2) but you decide on which you want to do.

So, the malachite itself has impurities in it that will make your paint look brown and blotchy but this can be overcome by separation either before grinding in medium or after.

This set of colours is about particle size. You can tell from the photographs you have already see of malachite that the finer you grind it, the paler it gets. Here, I took the dry pigment and put it through the sieve quickly so that the coarser grains of pigment would be left. I then ground them in some medium, painting an area that you can see on the right as the process went on. The viscosity of the medium was a limiting factor as when the particles became really fine, it protected them from getting ground any finer. I ended up watering down the medium a bit to get the finest sample.

- Machine ground pigment - I couldn't get anywhere near to this as the viscosity of the medium protected the pigment.

- This is barey ground and is there for illustrative purposes only. You can see that the pigment is large chunks with a bit of powder colouring it but it does have a very nice green colour.

- This one still has bits in it and is still on the coarse side for painting but it is getting there.

- This is fine as far as hue and saturation go but it is still on the coarse side for painting.

- This is good for painting but you can see that the saturation is starting to go.

- This was as fine as I could get and you can see that it is starting to look a bit grey when compared to the two above it although it is nothing like as fine as the next sample - the machine ground standard (0).

So, you do need to grind it but you can see that there is an optimum particle size before the satuarion starts to drop off.

All images and original artwork Copyright ©2017 Paul Alan Grosse.