Gold Punchwork

Whether it is icons or frames, punchwork has a significant role in the artwork.

Gold leaf when burnished is very directional in the way that it reflects - with the right ground, it can be like a mirror. This means that the area that is covered in gold appears dark, over large areas of it apart from where there is something light in front of it. If the main illumination for the artwork is similar to that used on most art, then it will be largely featureless.

Punchwork, such as that in the icon on the right, increases the angle at which the gold will reflect the light source towards the viewer. In a way, it is a similar process to normal paints except that normal paint takes incident light and colours it then reflects it in all directions whereas punchworked gold takes the light source, colours it and then reflects it towards the viewer. Using punchwork is similar to diapering insofar as it takes an otherwise falt area and gives it meaning.

The icon on the right has a sunken field with extensive punchwork (4.3x5.0" 10.8x12.7cm). It is painted on a hand-carved, solid, quarter-sawn oak support which has been gessoed over linen then gilded over bole then had punchwork applied in the two halos and the outer border. The outer edge of the border is painted with red bole and the pigments in the colours used are: cinnabar; carmine; gold ochre: yellow ochre; raw umber dark (not burnt umbre); lead tin yellow I; malachite; lapis lazuli; lead white and lamp black.

Without the punchwork, it would be quite mundane as overall the gold would be quite dark, except for a blurry reflection of the viewer.

This is a closeup of the halos with the border, showing that the halos are not the same as each other and how the border gold goes down what, if it were a separate frame, would be the sight edge, to the picture.

In the first image, you can see that the mother's halo goes up the slope of the 'sight edge' to the punchwork on the border and invades its territory a little. This is seen on many icons and is sometimes interpreted as a mistake.

However, it is not. The reason why it is supposed to do this is because paintings are a view into an alternative universe and the frame, as the name suggests, is like a window frame. The frame acts as a boundary between the alternative universe and the real world. By crossing over the boundary that the frame creates, it invades the real world a little, giving the idea that what you see in the painting is a little more part of the real world than it is in other paintings.

Here is a view of the bottom left of the border. You can see that the pattern takes a relaxed approach to going around the corner. The internal corner of the border - the 'sight edge' slope - is rounded and not a sharp corner like it is on the inside of picture frames that are made by cutting up long thin pieces of wood and joining them to form a separate frame. When people started making icons, the frame and the image that it enclosed were painted on a one piece albeit often made up of several pieces of wood.

You can also see that there are what looks like hemispherical indentations, circles and concentric circles.

Each one of these catches the light and glints back at the viewer.

Here are two concentric circles from the upper left 'sight edge' of the icon. The slope into the sunken field can be seen at the bottom of the image.

I have included a 1mm long bar to show you just how small in fact these features are. The inner circle is around 0.5mm across.

In the centre of the image is one of the deeper punch holes which is around 0.5mm across and a smaller, normal punch hole at around 0.2mm.

Despite calling them holes, each one is roughly hemispherical and because of the construction of the icon, the gold leaf stretches all of the way to the bottom of the hole with a mirror-like shine.

So, how does the icon manage to allow this sort of thing to happen without the ground simply falling off the wood or, for the larger holes, without making holes in the wood?

The answer is in the construction of the surface of the icon.

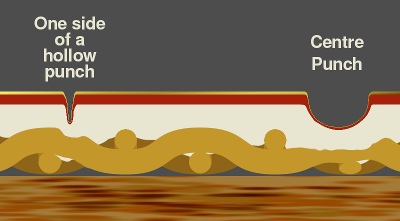

On the right, You can see a diagram of a cross-section of the surface - not to scale.

In the middle, the layers are as they are when the surface has not been modified by anything other than the burnisher. Note the interstitial voids within the weave and how the gesso only needs to go into the linen - it does not need to go all of the way to the wooden support.

On the right is a representation of what happens when the punch is used to make a hemispherical hole. You can see that the layers are pushed down into the voids. The fact that the gesso is powder sandwiched between a resilient layer of linen and the surface which is bole and gold held in place by glue. As it is on the sub-millimetre scale - holding a total mass in the order of tens of microgrammes - it is not subject to accelerations and other forces that are likely to make it fall apart.

On the left, you can see how the circle punch does pretty much the same but is less disruptive.

1. Gold leaf 2. Red Bole 3. Gesso Ground 4. Linen with Glue 5. Wooden support

So, what type of tools do we used to make these indentations?

The circular indentations are made with a set of hole punches - these are made for working with leather. They range from 0.5mm to 5mm in diameter, nominally in 0.5mm steps.

Whilst they are undoubtedly sharp enough for cutting leather, they are not so sharp that they damage the surface as you can see from the two concentric circles in one of the photographs above.

The area of these smaller punches - up to around 3-4mm - is small enough for you to be able to use the punch just by pressing the end of it into the surface manually.

There is no need to use a hammer with punches of this size.

Here, you can see the ends of the punches and also the centre punch that I use that creates the hemispherical indentations.

The normal holes of between 0.2 and 0.3mm can be produced fairly easily but the larger ones of around 0.5mm need a little more force - still no need for a hammer.

The centre punch is a cheap one from a local DIY shop and is fairly blunt compared to the sort of thing that you might find in a metalworking workshop. However, its rounded end makes it ideal for punchwork.

So, how do we prepare the ground for an icon?

First of all, select your piece of wood. I prefer to work with quarter sawn oak because it doesn't warp and because it is nice and hard so you can work it with a chisel without falling foul of all of those softwood-related problems such as vastly different hardness between the rings and so on.

Cut it to the right size and mark it out so that you have a reasonable border.

Then, get out your wood carving chisels and take out a nice little furrow around the border.

The one here curves around 90 degrees in 8mm which is about the right size.

Next, use one that is almost flat - a slight curve of around 1mm central displacement from flat - to take out the middle and leave it flat.

The slight curve on the blade means that you don't have the ends of the blade tearing out the grain at the side of the cut. This makes it all a lot easier to do.

Next, use a knife or a sharp point to score diagonally across the surface so that when you do the next step, the glue has something to hold onto other than the grain.

Now, cut some linen cloth so that there is half an inch to an inch spare around the edge. Make sure that there are no bobbles, or other lumps in the cloth.

Some people use muslin but unless you are not going to do any punchwork or your icon is really very small (less than a couple of inches high) you are better off using linen

Next, get your glue and using a brush apply a quick coat to the surface of the wood so that: it soaks into the surface, leaving no dry bits; and, the internal corners are filled with glue.

Wet the linen with the glue then squeeze it so that most of the glue comes out of it but it is all wet with it

Then, lay out the cloth onto the wood and push it onto the surface all over so that:

- The cloth lays flat on the wood;

- There are no folds in the cloth;

- There is not too much glue in the cloth;

- There are no foreign bodies trapped between the wood and the cloth;

- There are no foreign bodies lying on the surface of the cloth;

- There are no air bubbles under the cloth;

- There are no globs of glue in the internal corners under the cloth; and,

- The surface of the cloth is smoothed out.

Put it horizontally in a safe place and leave it a day or so to dry out properly so that it ends up looking like the image on the right.

Once it has dried out, carefully cut away the spare linen from the edge so that it is flush with it.

you should really cut away most of it first time around and then gradually work towards getting it flush rather than trying to do it all in one go.

One thing you should be careful to avoid is separating the linen from the wooden support when you are cutting the linen. This can be done if you are using a force that can pull it away such as if you have the scissors at the wrong angle. Don't worry too much if it dies happen as you can always put a bit of diluted glue there to stick it back again

Now that the gesso has hardened, sand away any little mountains with some coarse sand paper and then get it reasonably smooth. On the insides of the 'sight edge' use sand paper but also consider using riffler files. These are made for taking burrs of castings and are short and curved so this makes them ideal for evening out the shape of the 'sight edge'.

Next, use a scraper to take off the final irregularities and transform it into a mirror finish. I use a wide (100mm or 4") and a narrow (25mm or 1") wallpaper scrapers to do this. You can buy the proper scraper if you can source them but it is cheaper and easier to select some good scrapers carefully, finding ones that have straight edges and have no burrs, then using a 1,000 grit diamond slab to make sure they are smooth.

Carefully scrape the surface of the ground until it is flat. In the last stages, you can sprinkle some graphite powder onto the surface and rub it in lightly (do this outside as it get everywhere) and then as you scrape, it will reveal any bits that you haven't got to yet.

Next, mark out your image on the ground using silverpoint (pencil wasn't invented then) and a pair of dividers for any circles such as halos. Then paint with red bole wherever you are going to gild. Once the red bole has dried, mark out into the surface the boundaries of the gold with a sharp point. The gold will cover up anything you mark that doesn't cause an indentation.

Then, gild the surface and burnish it.

Finally, scrape away the red bole (and any gold) from any areas that shouldn't have gold on them.

Now, do your punch work. Inscribe any parts of circles you need using the dividers any straight lines with a steel ruler and a scribe and get to work.

Finally, you can paint the rest of the image in using whatever medium you want.

After that some people finish off the painting by rubbing linseed oil into the surface and letting it set over a few weeks.

All images and original artwork Copyright ©2019-2020 Paul Alan Grosse.